ORIGINAL ARTICLE PUBLISHED ON 2024-01-04

At the End of the Year, Many Set New Year’s Resolutions—But Most Struggle to Follow Through. This phenomenon, often called the “New Year’s Resolution Syndrome,” refers to setting goals but failing to achieve them—leading to disappointment and a diminished sense of self-worth.

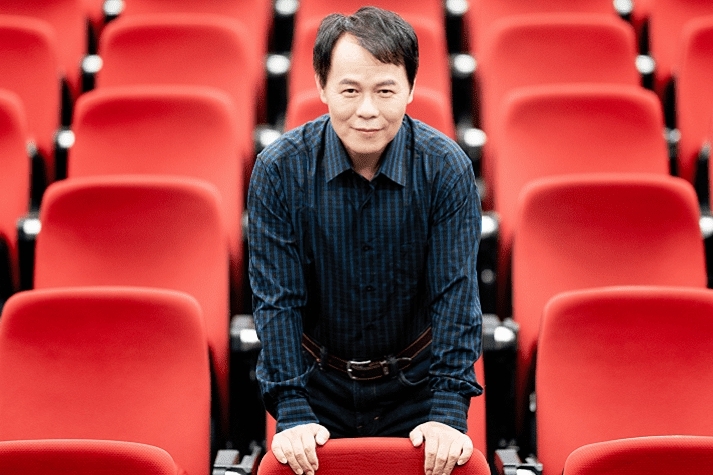

“Humans are creatures of habit—change is never easy,” says Professor Hung Tsung-Min, a research professor in the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences at National Taiwan Normal University. He points out that international studies have shown 80% of New Year’s resolutions fail by February. Clearly, it’s easy to plan but hard to follow through.

However, there are ways to overcome this cycle of giving up too soon.

Hung shares that our brains and minds are like muscles—they can be trained. When making New Year’s resolutions, you can apply psychological strategies such as setting “micro-goals” to boost your sense of achievement, using a “magnifying glass” mindset to recognize small progress, or applying the concept of “pacing” to enhance endurance and follow-through.

From Eight-Time National Table Tennis Player to Neuroscience & Sports Psychology Expert

Hung Tsung-Min is the chief of NTNU’s Sports and Brain Science Research Team and a legendary figure in Taiwan’s sports world. Coming from a poor family, he was selected by a teacher in elementary school to join the table tennis team. Just over a year later, he won a national championship, causing a sensation at the time.

When Taiwan’s Zuoying Training Center (now the National Sports Training Center) was established during his junior high years, Hung became one of its first athletes. He qualified for the national team for eight consecutive years, representing Taiwan in international competitions.

During his time at the training center, he came across a book about blood types, which sparked his curiosity. He began observing whether athletes’ performances differed based on blood type. He noticed that although national-level athletes often shared similar talent and training, their individual outcomes varied.

“Decades of Mental Skills Research and Olympic Athlete Coaching”

After retiring from competitive sports, he pursued studies at Fu Jen Catholic University, then at NTNU’s graduate school, and eventually earned a Ph.D. from the University of Maryland.

Upon returning to Taiwan, he focused on cognitive neuroscience in sports and established a psychophysiology lab. He was elected as a fellow of the American National Academy of Kinesiology—only the second Taiwanese person to receive the honor.

In addition to teaching, Hung applies scientific approaches to help train Olympic athletes. He recently published a book titled Breaking Through Inertia, sharing how to use psychological skills to step out of your comfort zone with minimal pain.

The Brain Is Energy-Hungry—Habits Help Save Energy

Why do so many people abandon their resolutions? Hung explains that from a cognitive neuroscience perspective, our outward behaviors result from millions of neurons interacting. Roughly half of our daily actions are habitual.

This is an evolutionary adaptation: the human brain makes up only about 2% of our body weight but consumes 20–25% of our energy. To conserve energy, we develop “efficiency modes”—automated behaviors like brushing teeth, getting dressed, or commuting—which are hardwired into our neural circuits after countless repetitions.

To form a new habit, you have to disrupt this inertia. For example, if someone usually relaxes with TV dramas after work, resolving to exercise instead means changing the default pattern. “Putting on sneakers and going for a walk” is less intuitive and requires more effort than simply turning on the TV.

Intentional Practice Is Key to Breaking Out of the Comfort Zone

Hung compares habits to rivers. Long-established habits are like well-formed rivers with stable courses. New habits are like tiny streams that need enough flow and repetition to carve out new paths—that is, to form new neural circuits.

To break inertia and step out of the comfort zone, you must engage your brain’s prefrontal cortex, which controls executive functions. This means making intentional choices. And when the new habit involves a skill—like learning English or playing the piano—it becomes even harder, because of the technical barriers involved.

Hard doesn’t mean impossible. Hung advises people to think about complementary strategies and develop their own achievement systems when setting resolutions.

Four Key Strategies to Build a Goal Achievement System

Key 1: Think from Three Angles, Create a “Profit & Loss Statement,” and Use Micro-Goals

When making resolutions, people often set overly ambitious goals. “It’s like trying to take a giant first step—you’ll probably fall or won’t be able to take the step at all,” Hung says.

He suggests first clarifying your real motivation by reflecting on the value, sense of achievement, and enjoyment the goal might bring. Then, list a “profit & loss” sheet: What benefits will come from taking action? What drawbacks from inaction?

This helps you think more critically. Hung stresses the importance of being careful when setting goals—frequent failure to meet goals can harm your subconscious self-efficacy and confidence. Sometimes it’s better not to set a goal than to set one and consistently fail.

Goals should also be specific and achievable. Use micro-goals—for instance, instead of “I want to lose weight,” say “I want to cut back on bubble tea.” Then consider your current behavior: If you usually drink five cups a week, set a micro-goal of cutting down by one cup. Once you succeed and feel confident, move to the next step.

Key 2: Use a “Magnifying Glass” to Notice Small Wins and Activate Positive Attention

As you work toward your goal, regularly use a mental “magnifying glass” to recognize progress. For example, if your micro-goal is to climb five flights of stairs a day and you succeed, give yourself credit.

Positive attention is also essential. Hung observes that many Taiwanese adults tend to focus on children’s mistakes. A child might score 98 on a test, and the adult immediately asks, “Where did you lose the 2 points?”

While understanding mistakes has value, overemphasis on shortcomings can lead to anxiety and self-doubt, and eventually learned helplessness. This leads to withdrawal and self-abandonment.

Hung advises giving positive feedback—notice your child’s efforts, improved time management, or willingness to communicate. Any improvement counts. Compare yourself to your past self, and even small progress should be celebrated.

Key 3: Minimize Feelings of Failure: Stay Flexible During Execution and Rehearse for Setbacks

Challenges are inevitable. Hung teaches techniques to help people stay on track and minimize feelings of failure.

One example is the “three-day average” method. If your goal is to climb five flights of stairs daily but you miss a day due to work or illness, adjust your target to “15 floors in three days.” Look at averages, not failure.

Also, stay flexible mentally: if you’re in an environment with no stairs, walk more instead. If Plan A doesn’t work, try Plan B.

Key 4: Use “Selective Review” and Build a Support Network to Amplify Success

Along with using a “magnifying glass,” Hung recommends using a “magic mirror” to affirm yourself. People who can self-affirm tend to be more motivated and positive.

He suggests doing a “selective review” before bed—recall what you did well that day. This boosts positive emotions and reinforces your belief in your abilities, amplifying successful experiences.

Humans are social beings and need external affirmation. In academic terms, this is academically called “Social Reward.” Find a group of like-minded people to share progress and encouragement.

For example, join a study group if preparing for an exam, or a fitness or diet community online. Sharing goals and progress with close friends or family can also help.

“When people have successful experiences, they gain confidence to keep going,” says Hung, who believes that “everyone has a key that can unlock the positive cycle of life.”

Source: Future Family / Writer: Chi-Ling Huang / Editor: Shih-Tse Hu (English Version Powered by ChatGPT, Edited by Serena H.)

照片提供:洪聰敏